Harry van Sprundel

CSRD Reporting: Building the Narrative

Part One

Introduction

In the era of escalating climate concerns, the demand for transparency in how organizations contribute to global climate goals has never been more critical. The Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), introduced by the European Union, represents a significant stride towards meeting these demands. The CSRD represents a shift in how organizations across the European Union are required to disclose their sustainability efforts. This directive is specifically designed to align corporate activities with the ambitious climate goals established in the Paris Agreement, ensuring that organizations are accountable for their environmental, social, and governance (ESG) impacts in a transparent and standardized manner. CSRD is not just another reporting requirement; it is intended to become part of the annual report for ESG matters, serving as a comprehensive reflection of how a company has performed and how it plans to perform on sustainability issues. By integrating ESG reporting into the core of corporate accountability, the CSRD aims to provide stakeholders with a clear, consistent, and reliable picture of a company’s sustainability journey, both retrospectively and prospectively.

Unlike other ESG-related reports, the CSRD emphasizes much more on qualitative data over quantitative metrics, providing a more comprehensive narrative of a company’s sustainability practices. This approach allows for a deeper understanding of how businesses are addressing complex issues such as climate change, social responsibility, and governance ethics. By moving beyond mere numbers, the CSRD aims to paint a fuller picture of corporate sustainability efforts, fostering greater accountability and informed decision-making among stakeholders and it forces organizations to formulate their ambitions related to ESG topics.

This directive emphasizes the need for organizations to not only disclose their current performance but also to outline their future strategies and commitments towards sustainability, making it a cornerstone of modern corporate reporting. To meet these rigorous demands, companies will need to rethink and adjust their existing processes, systems, and (business) operating models to fully integrate their sustainability efforts into their current business landscapes. This integration is crucial for ensuring that sustainability is not treated as a separate entity but is embedded into the very fabric of the organization’s operations and strategic direction.

European Sustainability Reporting Standards

In May 2024, the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG) finalized twelve European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS). These standards have been designed to help organizations to comply with CSRD reporting which will take effect in FY2024.

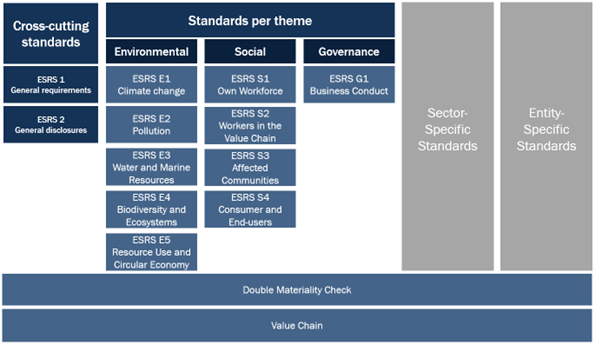

The twelve ESRS which have recently been finalized by the EFRAG are split into several topics. ESRS 1 and ESRS 2 cover respectively general requirements and general disclosures. These standards are crosscutting the different ESG themes. The remaining ESRS are all standards per theme. ESRS E1-E5 cover environmental topics, ESRS S1-S4 cover social topics and finally ESRS G1 is related to business conduct.

Next to these standards that apply to all companies that must comply with CSRD, there are also sector specific standards. The sector-specific standards have recently been postponed and are planned to be published in June 2026. Finally, there could also be entity-specific disclosures. For impacts, risks and opportunities (IROs) that are deemed material by the organization, but which are not covered by the topical standards, the organization will develop disclosures themselves for this in in line with the mandated ESRS.

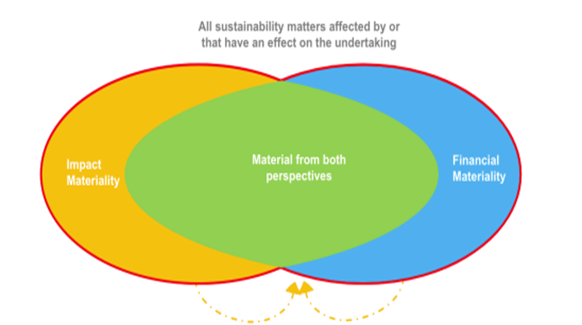

Double Materiality

A crucial concept within the CSRD framework is double materiality, which requires organizations to assess the materiality of each sustainability matter relevant to their sustainability report from two perspectives: financial materiality and impact materiality. Double materiality means that organizations must determine whether a topic has significant financial implications or a substantial direct impact on society and the environment. It is up to the organizations themselves to decide which topics are deemed material, but they must provide clear explanations for their decisions, whether a topic is included or excluded. Often, matters deemed material exhibit both financial and direct non-financial impacts, leading to a significant overlap. However, there are instances where a topic may be material solely from a financial standpoint or only due to its direct impact on society and the environment.

Value Chain

In addition to the materiality assessment, the CSRD imposes a comprehensive value chain reporting requirement on organizations. Specifically, organizations must report on all material impacts, risks, and opportunities (IROs) that arise or may arise within their value chain. Annex 2 of the Delegated Act on this topic describes the value chain as: “the full range of activities, resources and relationships related to the undertaking’s business model and the external environment in which it operates”. This definition means that organizations should consider their upstream activities, downstream activities and their own activities.

Organizations are not required to include value chain information on all disclosures, but only when it’s connected to IROs that have been identified as being material, or when it’s specifically required by the disclosure requirements.

The regulation prescribes that organizations will have to make reasonable efforts to collect primary information on the actors in their value chain. However, when they can prove this is not reasonably possible then the organization is allowed to make use of estimates such as proxies or sector data. The reason for requiring the disclosure of the value chain is that often IROs arise not in the company’s own activities, but rather in their upstream or downstream activities. By having to report on the whole value chain, a full picture is drawn of a company’s impact on sustainability matters.

When considering the value chain, there are distinct differences between financial institutions and corporates. For corporates the upstream and own activities will often be very relevant, but for financial institutions, the focus is particularly on downstream activities, which primarily relate to their financed assets. The relevance of the financials’ downstream activities is true for their wholesale lending as well as their real estate lending, where institutions must consider the type of real estate they finance and the incentives they provide to borrowers to improve the energy efficiency and emissions profile of these properties.

Understanding and reporting on these downstream impacts is critical, as they represent the bulk of the environmental footprint for financial institutions and are key to aligning with broader climate goals.

Deep dive on the data points

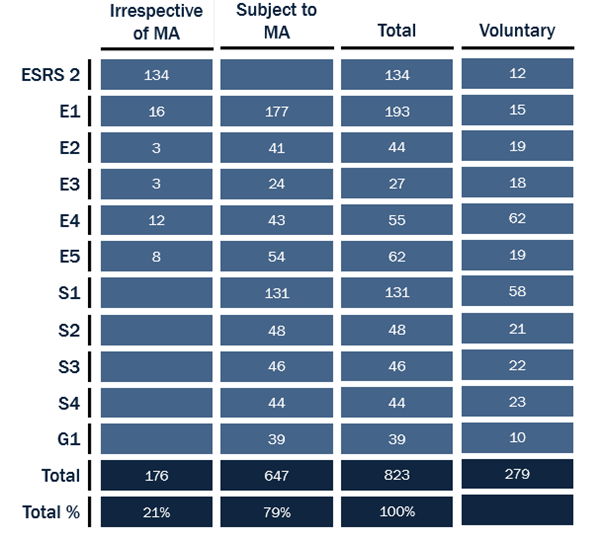

In the final publication of the data points for the ESRS, comprehensive details were provided for 11 of the 12 standards. ESRS 1, which comprises general guidelines, does not include specific data points and is therefore excluded from this detailed enumeration. The publication revealed a total of over 1,100 data points, designed to guide organizations in their sustainability reporting efforts. Of these, roughly 25% are voluntary, offering companies the flexibility to report additional information at their discretion. The remaining 75% of the data points are mandatory, ensuring a robust and consistent approach to sustainability disclosures.

Within the 823 mandatory data fields, there is a crucial distinction based on the materiality assessment. A subset of 176 fields must be disclosed by all CSRD reporting companies, irrespective of whether the topics are deemed material to their specific operations. This ensures that essential sustainability information is uniformly reported, providing a baseline of transparency and accountability across all reporting entities. The other 647 mandatory fields are contingent on the materiality of the sustainability matters; they must be reported only if they are deemed as material by the organization, following their double materiality check. This structure allows companies to tailor their disclosures to reflect the most pertinent issues, balancing comprehensive reporting with relevance and practicality.

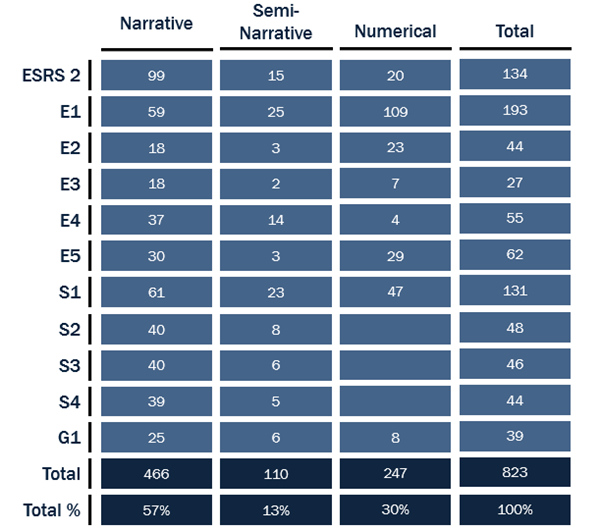

Of the 823 mandatory fields, 466 are narrative-type fields, which require organizations to provide detailed descriptions and qualitative information. An additional 110 fields are semi-narrative, combining elements of both qualitative and quantitative reporting. The remaining 247 fields are numerical, necessitating the collection and reporting of specific quantitative data.

The relatively low proportion of numerical fields, at just 30%, highlights the CSRD’s emphasis on detailed, organization-specific reporting. This focus on narrative and semi-narrative fields ensures that each report captures the unique aspects of an organization’s sustainability efforts. However, we argue that the rigorous collection of numerical data is crucial. Establishing a stable and accurate basis for these numerical fields can greatly facilitate the preparation and explanation of the more complex narrative and semi-narrative disclosures. By grounding their reports in solid quantitative data, organizations can provide clearer, more coherent narratives, ultimately enhancing the overall transparency and reliability of their sustainability disclosures.

How quantitative data points support the qualitative data points

The relationship between quantitative and qualitative data points in CSRD reporting is deeply interconnected, as illustrated by the requirements of ESRS E1 and ESRS E2. For instance, ESRS E1 mandates organizations to explain their transition plan for climate change mitigation, which must include greenhouse gas (GHG) emission targets—a quantitative metric essential for tracking and reducing carbon footprints. To set these targets accurately, an organization first needs a precise understanding of its current GHG emissions, necessitating robust quantitative data collection. This baseline data provides the foundation for setting realistic and achievable targets. Concurrently, qualitative data is crucial for documenting the strategies, policies, and actions underpinning these targets. By detailing how the organization plans to achieve its GHG reductions, qualitative information complements the quantitative metrics, ensuring a comprehensive approach to climate action.

Similarly, ESRS E2-1 requires organizations to explain whether and how their policies address various types of pollution, such as air, water, and soil pollution. This qualitative disclosure is complemented by ESRS E2-4, which mandates quantitative disclosures on these same pollution types. This dual requirement demonstrates the importance of having accurate quantitative data available and the right data architecture in place. By combining quantitative and qualitative data, organizations can provide a complete and transparent account of their environmental impact and the effectiveness of their pollution mitigation strategies. This synergy between quantitative and qualitative data ensures a more effective and transparent sustainability reporting process, ultimately driving better environmental performance and accountability.

Overlap with other regulatory reporting requirements

There is significant overlap between the data points required by the CSRD and those needed for other ESG reports, making it even more beneficial for organizations to have a robust data architecture in place. For example, both the CSRD and other frameworks, such as EBA Pillar III, require the disclosure of GHG Scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions. This overlap means that by collecting and managing this data effectively, institutions can meet multiple reporting obligations simultaneously. Additionally, there is a shared focus on physical risk requirements across these reports, where organizations must assess and disclose the potential impacts of climate-related physical risks on their operations and assets. Beyond these quantitative data points, EBA Pillar III also mandates qualitative disclosures that, while more generic, align closely with part of the qualitative requirements of the CSRD. These qualitative aspects often involve narrative explanations of an institution’s risk management strategies, governance structures, and sustainability goals, all of which are critical to both EBA Pillar III and CSRD compliance. By ensuring a solid data foundation, organizations can efficiently address these overlapping requirements, reducing redundancy and enhancing the overall quality of their sustainability reporting.

Continue reading and find the second part of this series here.

Want to know more?

We like to talk about our business and how we can help you!